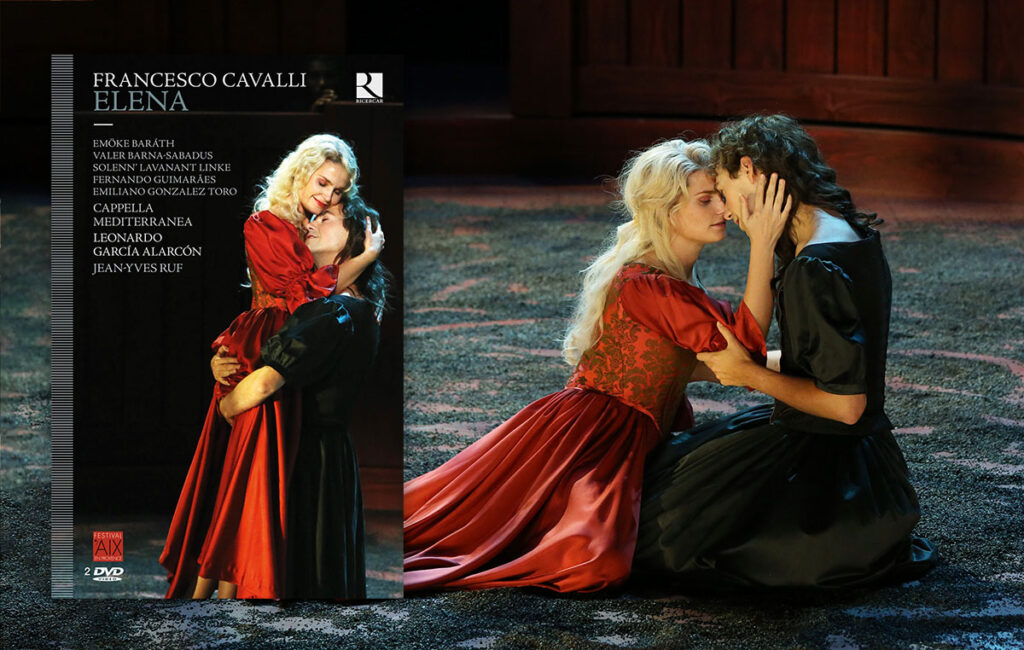

“The elegance of the costumes and the cleverness of the recording – with its close-ups of the performers, which underline the pathetic effect of their always-precise declamations – also contribute to the success of this recording.”

Jean-François Lattarico for Diapason

Elena reveals was written at a time when opera librettos were being “humanised”. After the prologue and the first scene, the ancient gods disappear and are replaced by four human beings driven by desire for the most beautiful woman in the world. The lust she inspires gives rise to a comic scenario in which Menelaus, disguised as Elisa, unwittingly awakens the libido of King Tyndareus and the hero, Pirithous. This scenario plays on the particularities of the castrato’s voice. As it is close to the female voice in tessitura and timbre, it allows for the gender ambiguity and cross-dressing that regaled a Venetian public always fond of carnivalesque disguises.

But Menelaus’ disguise does not only give rise to the usual misunderstandings. It also infuses the play with a homoerotic dimension that is omnipresent in the Venetian tradition. For example, we can draw several parallels with La Calisto, which also based on a libretto by Giovanni Faustini. Jupiter metamorphoses into Diana in order to seduce the nymph Calisto, who expresses his love for the goddess–hunter. Like in Elena, the story of a secondary couple develops in parallel to the central love story (Diana/Endymion in La Calisto, Theseus/Hippolytus in Elena). They are accompanied by a number of more or less typical secondary characters, including the elderly maid who complains that she does not arouse desire like her mistress (Erginda, then Eurite), the jester who laughs at everything (Iro) and the decrepit king who sighs for love like a young man (Tyndare).

“We have been eagerly awaiting this new recording of Elena after the enchanting production at the Théâtre du jeu de Paume in Aix-en-Provence last summer. When it premiered, we were struck by the homogeneity of the reading, which revealed a prolific score that is surely one of the richest and most seductive work by the Venetian master. […] Although comedy is more present here than in established masterpieces like Poppea and Calisto, we can still recognize the mixture of genres in the pathetic and heart-rending lamenti of Ippolita, the sensual duets of Elena and Menelao and the disenchanted facetiousness of Iro, who questions our fragile humanity with derision.

To bring this forgotten score back to life, Leonardo Garcia Alarcon has assembled a flawless cast. Emöke Barath radiates beauty and grace. Valer Barna-Sabadus has the physique and voice for the job, as does the irresistible Emiliano Gonzalez-Toro, who proves to be an outstanding actor. Even the secondary roles are sumptuously cast (Mariana Flores is imperial). If Rodrigo Ferreira’s singing at times seems a little (too) tense, all the singers do justice to this theatre of the senses with impeccable diction and dramatic commitment. Jean-Yves Ruf’s soberly linear reading has the great merit of making the usually complex plot immediately legible. The unique wooden set, with its warm colours, evokes both Shakespeare’s Globe and a battle arena that the two protagonists and almost all the secondary characters must surrender to. The elegance of the costumes and the cleverness of the recording – with its close-ups of the performers, which underline the pathetic effect of their always-precise declamations – also contribute to the success of this recording.”

Jean-François Lattarico for Diapason

See full article

Why is Cavalli’s Elena only being rediscovered today?

“I’ve asked myself the same question many times! How can a work of this quality go 350 years without being performed? It’s not just the musicians’ fault. Unfortunately, some directors content themselves with works that have already been recorded, perhaps out of a lack of curiosity or access to manuscript sources. If you are not a musician, it is difficult to imagine what a score might sound like. When we were preparing the premiere of Cavalli’s Elena, Jean-Yves Ruf came to my place, and I played the score for him on the harpsichord for three days so that he could record me and have a sense of the music to talk about it with his team. The director has to have a lot of imagination. He has to keep in mind what he knows about Monteverdi and Cavalli’s well-known compositions, then throw himself into the void with an unknown piece of music. […]”

Interview with Leonardo García Alarcón by Jérémie Leroy-Ringuet

***

This work describes the power of desire, a theme that can already be found in Monteverdi’s Coronazione di Poppea. Is it typical of Baroque art?

“The Baroque notion that everything is in motion is omnipresent in Elena. No love story established at the beginning will last throughout the action. At the beginning of the play, Elena is a virgin who wants to experience love. When Menelaus arrives and questions her, she gets close to him when he is disguised as Elisa. I’m fascinated by the relationship that develops between this young girl and this man disguised as a woman. There’s something rational about it, but at the same time there’s that irrational world where bodies speak to each other and recognise one another. This idea is already present in Monteverdi’s Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. Clorinda dons armour and comes face to face with her lover, Tancredi, who doesn’t know that he’s fighting his own fiancée. He just knows that it has something to do with that particular body, something that remains strong, whether in death, in life or in hatred. Menelaus’ desire and Elena’s gaze upon Elisa make the intimate relationship between the two of them magnificent. Elena is troubled, even if it doesn’t show on the surface. […]”

Interview with Jean-Yves Ruf by Marie Goffette

Produced in association with M_MEDIA / CLASSICAL.tv